It is undeniable that Henry Flagler’s Over-Sea Railroad altered the history of the Florida Keys. One of the things it accomplished, at least for islanders who had historically relied on the Atlantic Ocean to engage the outside world, was to turn their focus away from the long, thin docks extending out from the shoreline. Instead, they turned to the railroad right-of-way established along the interior of the island chain.

The train made commuting to and communicating with the outside world reliable. The train to Key West proved culture-changing, too. No longer was the island chain only accessible by shallow-draft schooners. Now, a train was roaring up and down the island chain, twice a day, and offering scheduled deliveries of mail, ice, and sundry items like flour and coffee, as well as the convenient arrival of family and friends.

Though the Key West Extension of the Florida East Coast Railway became the first conduit to link the mainland to the island chain, it was not the last. The next would become State Road 4A, more commonly known as the Overseas Highway. Less official names for the road included the Fishing Route, because the road led to the fertile fishing grounds surrounding the islands, and Old Bumpy, a local name based on the fact that for every mile one drove along the road, the car (and its passengers) bounced a half-mile up and down.

Whatever it was called, the road was an instrumental component to the development of what would become a staple to the economy of the Florida Keys, tourism. Chairman of the Monroe County Commission J. Otto Kirchheiner is credited as the first person to traverse the inaugural Overseas Highway, driving from Key West to the mainland on July 18, 1927. The road would officially open to public transit on January 25, 1928.

The original road entered the Keys via what is today Card Sound Road. It is also the path that passes by Alabama Jacks, home to some of the most famous conch fritters ever to be fried in the Sunshine State. Version 1.0 of the Overseas Highway was a far cry from the strip of asphalt and concrete people drive down today. It was longer, followed a less precise track between Key West and the mainland, and it was incomplete.

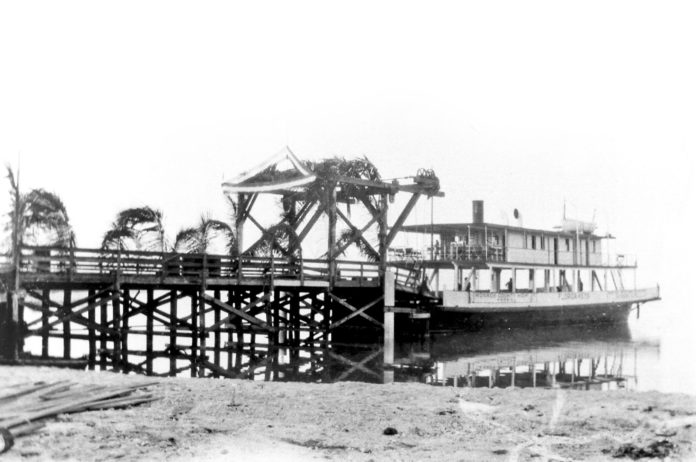

An automobile ferry system was used to bridge a 40-mile gap in the highway. When driving from the mainland, the road came to an end at a ferry terminal on Lower Matecumbe Key. Three ferries had been purchased from Gibb’s Shipyard in Jacksonville for $850,000. Each was capable of transporting 20 cars at a time. Vehicles less than 14 feet long were charged $3.50, while those longer than 16 feet cost $6.50. Ticket prices included the driver, but passengers were assessed an additional charge of $1 each. From Lower Matecumbe Key, the ferry traveled to No Name Key. The trip between the two terminals took about four hours, weather permitting. Ferries departed twice daily from both terminals, at 8 a.m. and then again at 1 p.m.

While it was possible to reach Key West in 1928, the Upper Keys were significantly more convenient for those drivers venturing from the mainland. Fishing camps, hotels and restaurants began to appear along the side of the road. That this first version of the highway was less than ideal was not a secret. To bring more cars to Key West, the ferry system needed to be eliminated. In 1930, officials brought in the Army Corps of Engineers to assess the costs associated with building a continuous system of automobile bridges to connect Key West and the mainland.

The resulting plans were submitted to the United States Congress under the project name “Oversea Highway” and had an estimated price tag of between $7.5 million and $13.7 million. The plan went unrealized.

The Overseas Highway 1.0 also ignored the Middle Keys. Circa 1932, road projects were funded that included two additional ferry terminals, one on Grassy Key and the other on Hog Key, as well as 13 miles of road to connect them. The collapse of the American economy and the emergence of the Great Depression thwarted further efforts to bridge the gap. Still, Monroe County officials held on to the belief that a solid bridge system connecting Key West to mainland America could represent a potential boon to the economy and, in 1934, a plan was set into motion. That story, the Overseas Highway 2.0, will unfold next week.