When historic and harmful ocean temperatures began ravaging our reefs and coral nurseries, Keys Marine Laboratory (KML) and coral practitioners stepped up to the challenge. Together, they’re working at a breakneck pace to safeguard hope, despite this record heat.

Coral restoration science actually began over a decade ago in the Keys with Mote Marine Laboratory and Coral Restoration Foundation (CRF) pioneering different restoration techniques. Since then, our local scientists and restoration practitioners have continued to push the forefront of this new scientific sector.

Under normal environmental conditions, offshore nurseries allow practitioners to grow corals en masse and under more optimal conditions. Over the years, dozens of coral nurseries have been established throughout the Keys to support restoration efforts; until recently, these were all full of endangered and important coral species, being grown out for eventual outplant back onto our degraded reefs.

Then June and July happened.

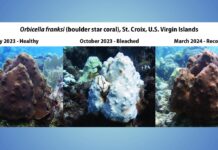

An unprecedented marine heat wave settled upon the waters. Ocean temperatures at this time of year are typically 85 degrees Fahrenheit; however, recent readings hit between 92 and 97, and a buoy in Manatee Bay – northwest of Key Largo – broke a world record by registering a jacuzzi-like 101 degrees. Our coral reef – the third largest barrier reef in the world and the lynchpin of our local economy – is suffering under this extreme heat, with many corals bleaching and/or dying. This includes wild and restored corals of all species, as well as coral fragments in in situ ocean nurseries.

The marine heat wave forced all restoration groups to act fast to save as many corals as possible; most decided to bring bleached and stressed corals from offshore nurseries to land-based facilities to save them from the extreme temperatures.

One of the safe havens is Florida Institute of Oceanography’s Keys Marine Laboratory (KML) in Layton. Hosted by USF, the scientific research field station supports researchers from various organizations and universities by providing marine biology expertise, saltwater raceways, boats and scientific divers. During this crisis, they’ve become the triage station for thousands of corals coming in hot and hurting from offshore nurseries.

“It is obviously disheartening to see all of this happening, especially in such a short amount of time. It’s painful to see, but we’re trying to see the silver lining,” said Emily Becker, Tavernier resident and KML’s seawater systems manager. “By providing this service for people to bring in coral and keep them in this facility where we can maintain optimal conditions, it brings me more hope.”

KML recently added new, state-of-the-art systems and raceways to its facilities. The field station now boasts 60 seawater tables, ranging from 40 to 4,000 gallons. They de-gas, sterilize and manipulate the temperature of raw seawater before it hits their tables. This eliminates large particles, bacteria and other pathogens, Becker said. The system also allows KML to mimic normal offshore reef temperatures, meaning the KML team can optimize their systems for temperature, pH and salinity to provide stable conditions for corals and other animals in their care.

“Ideally, we would’ve been able to test each component of our new system one-by-one, but this event made us test it all at once – and I am so happy to see all components doing what they’re meant to,” Becker said. “It’s allowed us to serve this critical role at this really devastating time.”

Currently, KML is holding roughly 1,500 corals from various coral restoration groups in its tanks; Becker estimates they have the ability to hold 3,500. Practitioners are also bringing corals up to the mainland to other facilities and using innovative transportation methods like CRF’s new “coral bus.”

The seawater systems expert noted with pride how practitioners will breathe a sigh of relief once they get corals out of the hot water and into KML’s tanks. “Because we’re here and we have these systems, they can take a breath, reassess and know that everything in the tables is okay,” she said. “They can make plans for the future. That’s been a huge positive.”

The eventual goal is to rehabilitate the corals in these controlled systems until temperatures drop and the reef is safe for them again. And, it’s working. When the Keys Weekly visited KML last week, Becker discussed pillar coral that came in stressed from CRF’s Tavernier nursery. The coral pieces came in paled and/or bleached on a Saturday; by Thursday, a few had regained their characteristic coral color – and, importantly, their symbiotic algae that give them this hue and the majority of their energy. Pillar coral is one of the most endangered corals on our reefs, so this is a great sign.

“These corals we have here, no matter how pale they are when they come in, if we can get them to a healthy point in the next weeks and months, this is the hope for the future of the reef,” added Cynthia Lewis, KML director. “This is what practitioners will be growing, restocking their offshore nurseries with and eventually outplanting. This is hope, right here in our raceways.”