Are we witnessing the death of an entire ecosystem?

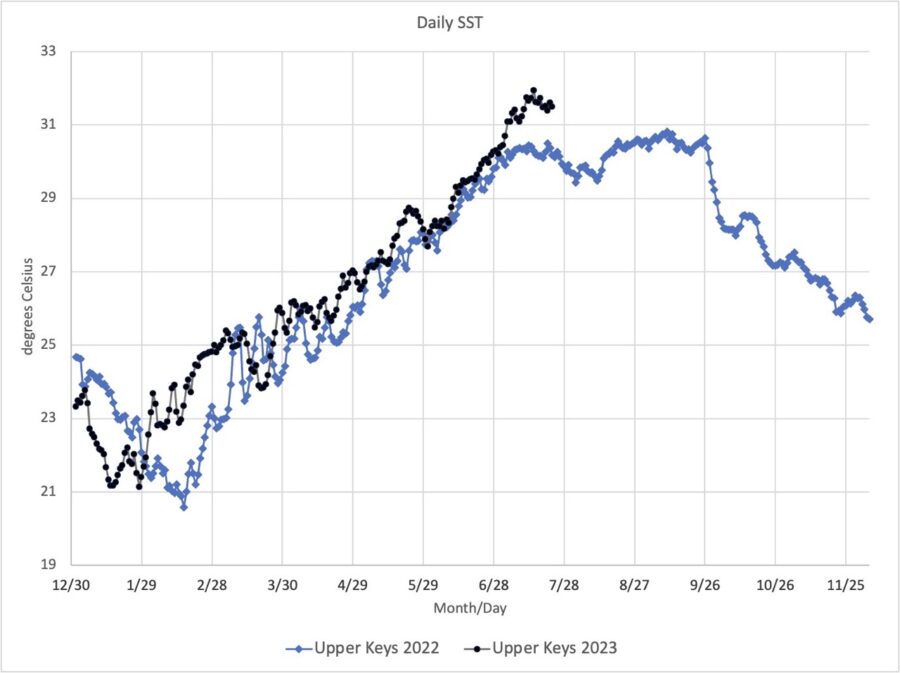

It’s too early to tell, but that’s the unbearable – and hopefully unfounded – fear in the back of many minds as historic water temperatures continue to decimate coral reefs and other fragile ecosystems the Keys are known for.

“The biggest unknown from this heat wave is what it could do to our habitats,” said Ross Boucek, the Florida Keys initiative manager at Bonefish and Tarpon Trust (BTT). “Lots of sponges are dying, corals are bleaching, and the heat is certainly stressing our seagrasses. In addition to these stresses on the habitats, the heat wave is causing fairly intense algae blooms in some places. We are in uncharted territory with this heat, so it is hard to predict what our systems will look like on the back end of this.”

In late June, an unprecedented heat wave (above and below the surface) began suffocating the Keys. This sweltering heat has intensified and stayed, causing catastrophic coral bleaching and death on most of the reefs throughout the Keys.

In a somber and urgent written statement, Coral Restoration Foundation (CRF) reported the “unimaginable – 100% coral mortality” in its Sombrero Reef nursery, where they’ve been working for over a decade. Additionally, CRF reported the almost complete loss of its Looe Key Nursery in the Lower Keys. They, and other restoration organizations in the Keys, are now “rescuing” as many corals as possible from in situ ocean nurseries and relocating them to land-based holding systems as a “last lifeline” for many species.

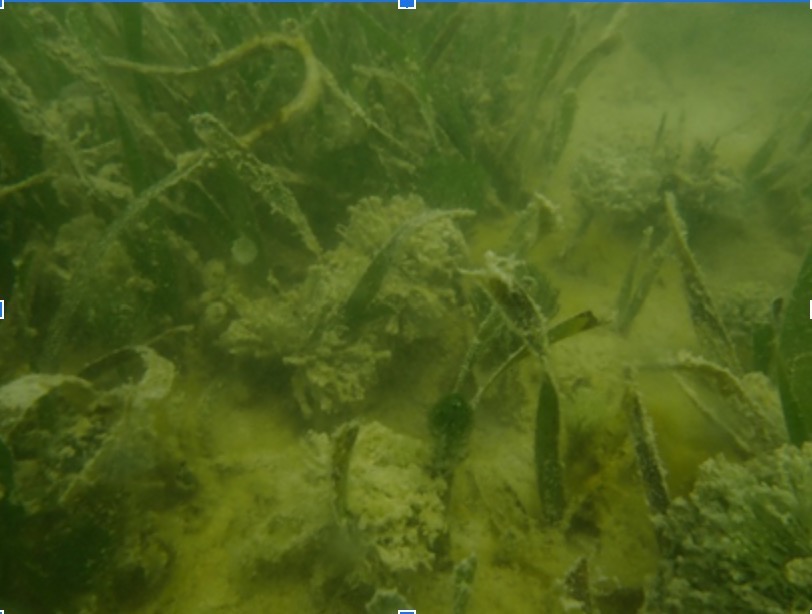

By mid-July, dead fish and sponges dotted our waters.

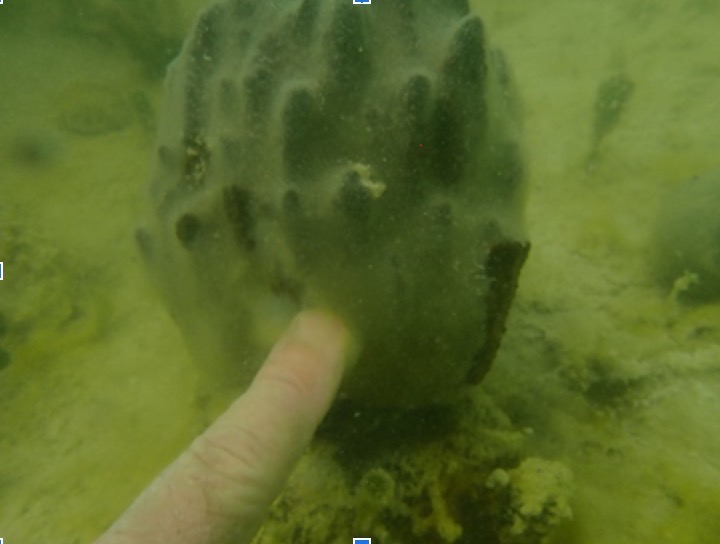

“The hot still waters cause a cascade of disturbances that harm numerous species in the nearshore hardbottom habitat,” said Tom Matthews, program administrator of Florida Fish & Wildlife Conservation Commission’s Fish & Wildlife Research Institute. “Poor water quality and increased sediment has caused the decline of this habitat for decades, but more frequent harmful algae blooms and now unprecedented and prolonged high temperature is causing the death of a broad array of sponges, soft coral (gorgonians), and even the few corals that are normally considered particularly hardy and resilient.”

Sponges are the “unrecognized water pumps and super filters of our marine ecosystem,” Matthews added. While limited saltwater facilities exist for corals, there isn’t enough capacity to rescue sponges. And, as hot water increases, the frequency and size of algae blooms that harm sponges has increased, and sponge restoration efforts have not been able to keep up, he said.

So, what’s going on? “Heat does a lot of things besides causing fish to overheat and die,” Boucek said.

“All plants and animals need oxygen to live,” Matthews added. Warm water holds less oxygen than cool water, and this year’s extreme temperatures have caused oxygen levels to decline below the levels needed by many species to live – causing their death.

Additionally, the hot water promotes the growth of phytoplankton and green algae that color our clear blue waters dark shades of lake green and brown, he added. While not harmful like red tide, they further deplete the water’s oxygen levels at night and smother sponges and corals.

Furthermore, excess heat without rain can increase evaporation and make some areas extra salty. This is really bad for seagrasses and Florida Bay, Boucek said. Finally, heat can kick bacteria and microbes into overdrive, breaking down organic matter and increasing nutrient loads. These increase algal blooms and further decrease oxygen – a dangerous positive feedback loop.

Mobile marine species aren’t necessarily faring better. BTT reported that most dead fish are tropical species that scientists expected would be more resilient to heat. In the nearshore hardbottom, dead fish include juveniles of important reef species like snapper, grunts and other ornamentals, Matthews said. The seagrasses, corals and sponges that are dying serve as critical nursery habitats for these species and many more, so the decline of the former is causing a cascade of ecological harms.

Bette Zirkelbach, manager at The Turtle Hospital, worries that the rising temperatures will also affect the sex determination of sea turtles during their incubation period on our coastlines. Warmer sand produces females, and cooler sand produces males, she said. “The last four summers in Florida have been the hottest on record, and the scientists that study hatchlings (baby sea turtles) have found no male sea turtles,” she added. “If sea turtles continue to hatch overwhelmingly as females, this could lead to a decline in genetic diversity within the population.”

Scientists throughout all disciplines urged that this devastating event highlights why it is so urgent to do everything we can to protect our sensitive habitats from local stressors like vessel groundings, anchoring, marine debris, declining water quality and overfishing – especially with mini-season upon us.

“Collectively, Monroe County cannot single-handedly change the trajectory of our climate,” Boucek said, “but we can do a better job of regulating, enforcing and educating boats to reduce vessel damage to sensitive habitats, and increase investment in local water quality improvement projects that will make our systems healthier and more capable of withstanding these events.” The community is waiting with bated breath, hoping for rains and a swift decline in temperatures. In the meantime, report fish kills and other concerns to FWC (email Tip@MyFWC.com, call 1-888-404-FWCC or dial *FWC or #FWC from a cell phone) and dead sponges, bleached corals, algae blooms, dead fish or fish gasping for air at the surface to BTT (email ross@bonefishtarpontrust.org).