For a third year in a row (okay, not counting pandemic 2020), team Florida Man crushed it. They took top prize in The Emerald Coast Open, the world’s largest lionfish tournament, held off Destin May 14 to May 16.

Marathon local Rachel Bowman is a member of Florida Man or, in her case, Florida Ma’am. The team collected 1,371 fish — or about 40% more than their closest competitor, the Stamps team. The other Florida Man team members are John McCain, Josh Livingston and Carl Antonik. Bowman has high praise for her teammates.

“Those guys are all technical divers and I learn a lot just being around them,” she said. “That’s how you become a better diver, by competing with people who are far more skilled than you.”

Also aboard the boat was Frauke Tillmans, research director for DAN (Divers Alert Network). She is studying the relationship between dehydration and cognitive function and took biometric measurements from the divers. The Florida Man team made a combined 87 dives over the two-day tournament.

“We made a concentrated effort to do shallower, shorter dives,” Bowman said, “just for our general health.”

The team was sponsored by Gary Graves of Keys Fisheries, also Bowman’s employer — she bartends at the restaurant and hunts lionfish for the wholesale side of the business.

145 divers from Destin, Florida, as well as those from around the country and even as far as Canada, descended on the panhandle for the tournament, which is hosted by Destin-Fort Walton Beach and Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. About $48,000 in cash prizes and $25,000 in gear prizes was handed out.

The tournament and festival was organized and operated by more than 50 volunteers from organizations such as Reef Environmental Education Foundation, Navarre Beach Marine Science Station and Tampa Bay Watch Discovery Center.

“It’s just so much fun,” said Bowman. “The crowning jewel of the tournament is just getting together with all of these people we haven’t seen in a few years. The lionfish world is a close-knit community and the opportunity to share and collaborate is really important.”

After the tournament, the lionfish haul is offered up for wholesale.

Are lionfish on the decline?

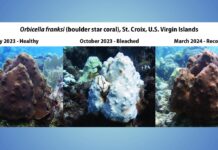

Two years ago, in 2019, the Florida Man team won the annual Emerald Coast Open Lionfish Tournament by catching 2,241 lionfish. In 2021, they took top prize with 1,371 fish. The numbers are declining and the culprit seems to be an ulcer disease.

“The number of lionfish has decreased, but recreational divers are not taking any credit for that,” said Rachel Bowman, a Keys-based lionfish hunter on the winning team (see sidebar). “Places where we used to find 350 lionfish, now there’s only 10 to 15. That’s good news for the environment.”

Lionfish are an invasive exotic species in the U.S.; they have no known predators and eat everything in sight. First spotted in U.S. waters in 1985, the ubiquitous presence of lionfish was well documented by the 2000s, giving rise to tournaments like the Emerald Coast and other measures to enlist the public to stop lionfish from proliferating. (While the fish have venomous spines, they make delicious eating when carefully filleted.)

The lionfish invasion seemed like an insurmountable problem until the fish started exhibiting an ulcerative skin disease, first spotted in 2017. Alex Fogg, who runs the Emerald Coast Open Lionfish Tournament, has also authored scientific papers about the population decline with Holden Harris, a doctoral student at University of Florida.

One study, published on nature.com in February of 2020, noted that commercial spearfishing catches declined by 50% in 2018 in the northern waters of the Gulf of Mexico. It also said that between 2016 and 2018, surveys conducted by remotely operated vehicles found that the lionfish density declined by 75% on natural reefs.

Fogg told the Keys Weekly that the disease spread more quickly in areas with a high density of bonefish. “It’s just like a kid with the flu in the classroom, compared to a kid at home with the flu,” he said. “Other places up and down the Eastern seaboard and in the Bahamas, the density of lionfish hasn’t changed that much.”

It’s important to note two things. One, lionfish available at local fish markets and stores like Whole Foods are still safe to eat. Two, the invasion isn’t over.