At about 5 a.m. on Nov. 18, 1822, the U.S. schooner Alligator hoisted its sails and began the slow move away from Matanzas, Cuba. It would be the final mission of the ship’s brief but storied career.

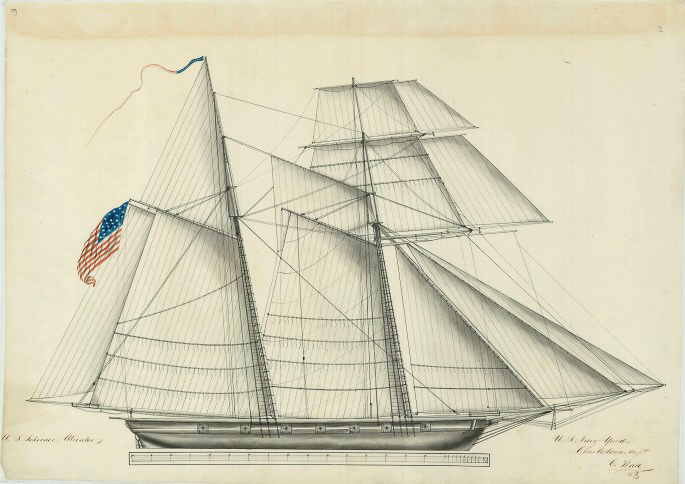

The Alligator was one of five swift 12-gun schooners built to serve the United States Navy’s anti-piracy West Indies Squadron. The two-masted, 86-foot ship-of-war was commissioned in March 1821. Some 19 months later, it led a convoy of ships liberated from a piratical attack away from Cuba and through the Straits of Florida. Virginia was the intended destination.

By 4 a.m. on Nov. 19, Lt. Dale, the Alligator’s acting commander, had lost sight of every vessel of the convoy but one schooner. On Nov. 20, the lone schooner was still the only ship from the convoy visible from the Alligator’s deck. Because the scuttlebutt suggested that the pirates the men of the Alligator had just engaged were going to attack the convoy’s stragglers, Lt. Dale issued orders to slow down.

At 8 p.m., the ship set its course north. Sounding weights were dropped every 30 minutes to determine the water’s depth. At 9:37 p.m., the schooner steered northwest. Three minutes later, the Alligator struck the Matecumbe Reef. According to the testimony of Victor M. Rudolph, acting lieutenant aboard the ship, “8 p.m. had no bottom at forty-five fathoms. At half past nine, she struck, at which time she was going five knots.”

Over the next three days, every effort was made to free the ship from the coral reef’s stony fingers. When a wrecker approached and offered assistance, Lt. Dale declined assistance but did ask the wrecker to hold the Alligator’s important papers – just in case. In hopes of freeing the ship, military manpower was exhausted, unsuccessfully attempting to dislodge the schooner. When one of the convoy’s straggling ships appeared on the horizon, a cannon, a small gun called a carronade, was fired. The blast served its purpose and attracted the attention of the Ann Maria.

By 10 a.m. on Nov. 23, whatever was left on the Alligator was loaded onto the Ann Maria, including its officers and crew. The Alligator was then “set afire fore and aft.” Because at least one keg of gunpowder had been left on the ship, at 3:30 p.m., what was left of the Alligator went kaboom!

While there are stories and stories about what led up to the events of Nov. 23, 1822, they will have to wait for another day. The story for this moment is where contemporary newspaper accounts recorded the site of the shipwreck. While the Alligator wrecked on the Matecumbe Reef, the reef was also identified as Carysford, a common early spelling of the legendary Carysfort Reef.

Carysfort is one of the oldest and most mature reefs in the chain. It has also been called the Florida Reef’s most dangerous tract of coral. The reef is said to have been responsible for one-quarter of all the wrecks that occurred during the early decades of the wrecking industry. Shallow and extensive, its jut out into the Atlantic for about four miles, making it a well-documented navigational hazard. It was one of the first reefs marked by the government after Florida became a U.S. territory in 1821, first by the lightship Caesar in 1826 and, in 1852, by the Carysfort Reef Lighthouse.

What those newspaper stories also revealed was that Carysfort is a name that was used in broad terms. Carysfort Reef is located about six miles off the coast of North Key Largo. It is well documented that Carysfort Reef was used as an umbrella term covering several barrier reefs in the Upper Keys that included those reefs growing in the shallows off of Key Largo, Plantation, Windley and the Matecumbe Keys. The Matecumbe Reef, located four miles off Upper and Lower Matecumbe Keys, grows 35 miles south of Carysfort.

A dozen prominent, shallow reefs grow between what is today Islamorada and North Key Largo. Because the record books were assigning the name Carysfort to such a significant stretch of the Florida Reef, it is easy to see why, at least on paper, the reef garnered such a perilous reputation. Though an absolute ship killer, its reputation has been enhanced by the broad use of its name. The Alligator, as well as scores of other ships, wrecked nowhere near Carysfort.

The U.S. schooner Alligator left behind more than stories when it wrecked on the corals in 1822. The site of the wreck, Matecumbe Reef, became known as Alligator Reef, home to the Islamorada icon Alligator Reef Lighthouse. For a time, too, it lent its name to Alligator Key. The small island was once described as “about a mile and a half long, elevated but two or three feet above the sea, and bordered with a growth of mangroves, upon which grow oysters and other mollusks.”

While Alligator Key has since washed back into the ocean, the spirit of the Alligator has remained a significant piece of Florida Keys’ history.