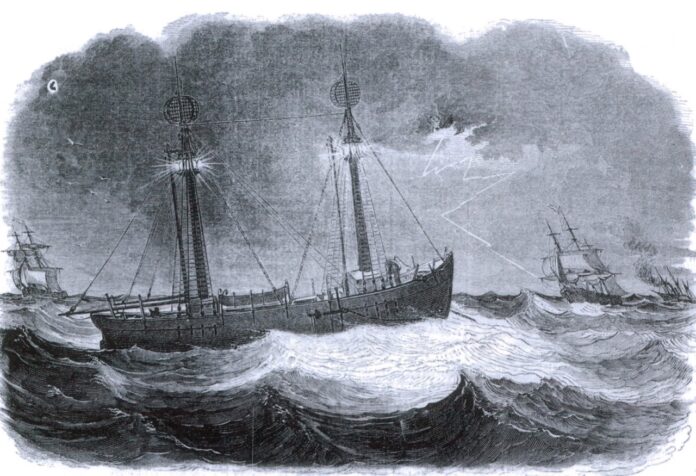

The Caesar was the first lightship to anchor at Turtle Harbor, where it worked to warn passing sailors of their proximity to the dangerous Carysfort Reef. The ship arrived in 1826 and only served a handful of years before it was condemned.

In 1829, Capt. John Whalton ordered the anchors brought in, employed the schooner’s sails, and set a course for Key West (and not for the first time). On May 26, 1829, the lightship Caesar arrived for repairs. After a survey of the ship was completed, the Collector of Customs, Mr. Pinkney, remarked that the Caesar’s timbers were “an entire mass of dry rot and fungus. I must say that there never was a grosser imposition practiced than by the contractor in this instance.”

The anchor, chains and sails were removed, and the hull was sold to a salvager named Fitzpatrick for $300. Congress allocated $20,000 for the construction of a replacement lightship. Named Florida, the lightship was anchored at Turtle Harbor and was first lit on Dec. 7, 1830. The ship served to warn passing mariners of their proximity to the large, shallow and treacherous Carysfort Reef.

Whalton transitioned from the Caesar to the Florida, where he remained until the day he died. Because food rations were somewhat limited aboard the lightship during its tenure at the reef, Whalton developed a garden on the shores of a cove on nearby Key Largo where he grew onions, tomatoes, melons and other fruits and vegetables to augment their general provisions. The area has since become known as Garden Cove.

On Oct. 5, 1836, as the second escalation of the Seminole War was ramping up, Whalton reported that Indians destroyed his garden. It was not the last time he would encounter the presence of Indians at the Key Largo garden. The following year, sometime in June, Whalton’s family sailed up from Key West to visit him on the Florida. The captain and four of his crew took their auxiliary boat to the cove for fresh fruit and vegetables, charcoal, or some combination of the two (depending on the account).

When they came ashore, the captain and his crew were greeted by a barrage of rifle fire from Indians who had watched them approach the cove from the garden. Four of the Florida’s men were struck, two mortally. Whalton and one crew member were shot dead on the beach. Two other crew members were wounded but were able to escape with the help of the lone member who escaped unharmed.

After Whalton’s death, a series of captains manned the helm of the Florida. One of the more colorful was Capt. Leonard Sistone, who abandoned his post one day and decided to get drunk instead. Charges against Sistone stemmed from the sworn testimony of Capt. R. L. Morris of the U.S. mail packet Hayne. According to Morris, when he sailed past Carysfort in the early hours of Oct. 19, 1841, the lightship Florida was not lit, and the only thing that saved him from wrecking was the fortuitous rising of the sun.

Morris went on to report that later that day, at Indian Key, Sistone was at the island, drunk, and that the lightship remained unlit on Oct. 20, too. The lightship captain was relieved of his duties and dismissed. While other captains would step in and command the lightship, the end of its service was in sight once construction of Carysfort Reef Lighthouse began in 1849.

The lightships were not always effective, as Navy Commander David D. Porter, of the U.S. mail steamer Georgia, pointed out in a letter dated July 1851. “On the reef near Cape Large, the floating lightship, showing two lights, intended to be seen twelve miles, but they are scarcely discernible from the outer ledge of Carysfort Reef, which is from four to five miles distant. On to (sic) occasions I have passed it at night, when the lights were either very dim or not lighted.”

The lighthouse sparked its light for the first time on March 10, 1852. On the 27th, the lightship Florida picked up its anchor, abandoned its post, and sailed for Key West. There, the ship was provisioned, and on April 13, the Florida sailed away from the harbor at Key West, hoping to make it all the way to Newport, Rhode Island. The Florida never arrived at her destination.

By April 17, things aboard the Florida had already begun to go awry, and the captain ordered the anchors dropped at Carysfort Reef to undergo repairs. Repairs were done as best as they could be made, and the Florida hauled up its anchors, hoisted its sails, and set a course for Charleston for further repairs.

The lightship Florida never arrived at Charleston. En route, on April 27, the Florida sank.