When Hanna Koch, coral reproduction scientist at Mote’s Summerland Key facility, talks about spawning, or coral sex, she gets excited.

Last year, Koch hit a huge milestone when the first “home-grown” batch of corals produced entirely from Mote’s own restoration broodstock spawned in her lab during the annual August coral spawning event. This summer, she and her team are celebrating another huge breakthrough: for the first time ever documented, Mote’s restored coral colonies have become parents out on the reef.

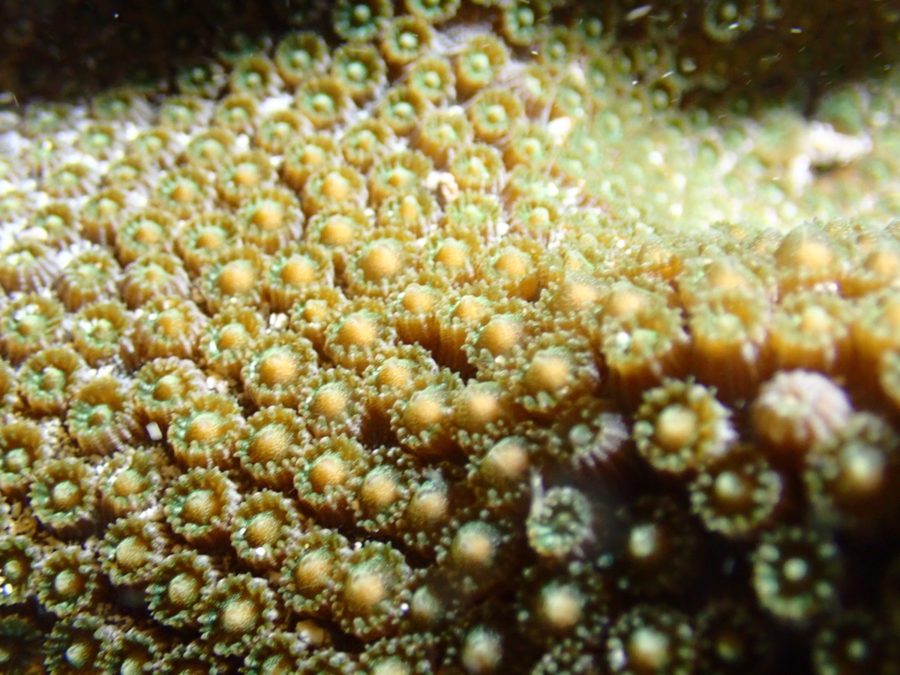

In July, Koch identified gamete bundles of egg and sperm in two different species of corals that Mote had restored to the reef, evidence of sexual maturity. It was then that she knew the corals were gravid, or “pregnant,” and ready to spawn, or “become parents” by releasing their gamete bundles.

This critical developmental milestone is the first sign that the restored corals are capable of producing new generations of corals on their own.

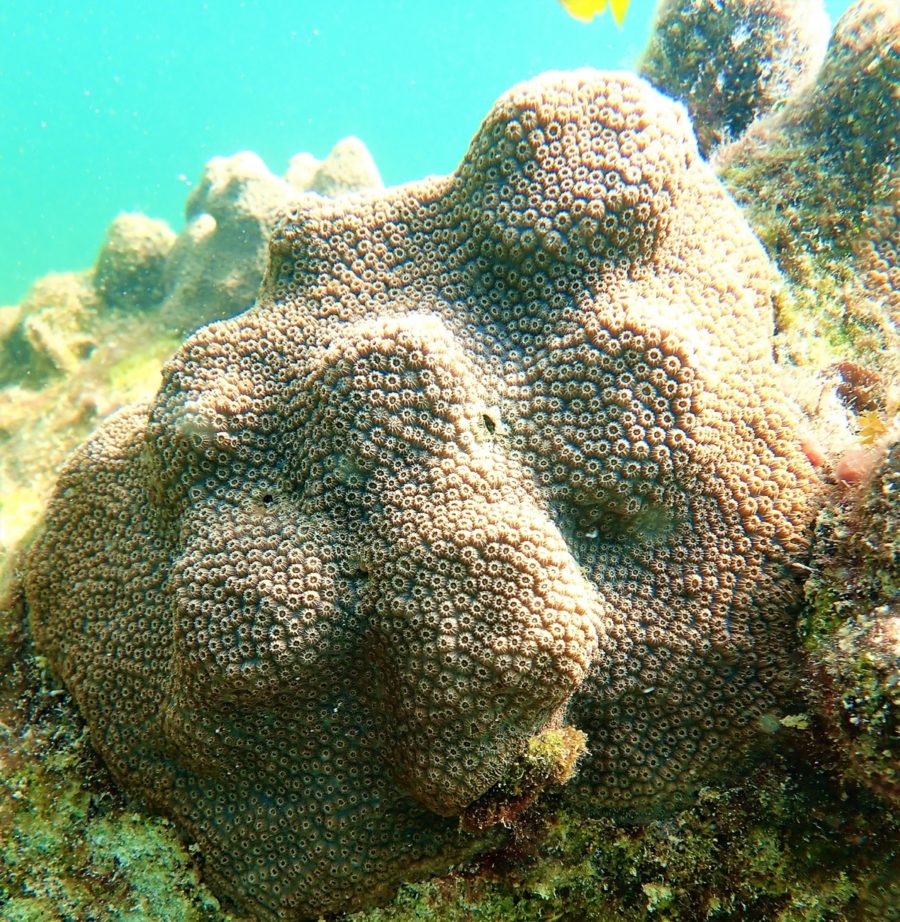

One of the corals is a massive or mounding species called mountainous star coral (Orbicella faveolata) and the other is a branching staghorn coral (Acropora cervicornis). Both species are listed as Threatened under the Endangered Species Act and are key, reef-building corals on the Florida Reef Tract. Both colonies were propagated within Mote’s land- and field-based nurseries, respectively, and outplanted at Newfound Harbor off Big Pine Key and Eastern Dry Rocks off Key West, respectively. The restoration sites are reefs in NOAA’s Seven Iconic Reefs program, sites that will receive a concentrated, collective effort of restoration support in the coming decades.

“We need corals to reproduce sexually for the survival of the species and for coral reefs as a whole,” Koch told the Keys Weekly. “Getting restored populations of key reef-building corals to a sexually-mature, self-sustaining state is a top priority of coral restoration scientists.”

As part of her research, Koch has been monitoring the survival, health, size and sexual maturation of these corals at both of these sites for the last three summers. 2020 is the first time she’s seen them gravid.

“I was both surprised and very excited, as I have been hoping they’d be sexually mature every summer I have monitored them,” said Koch. “But after negative results two years in a row, I wasn’t sure if or when these corals would become sexually mature, especially because there are a lot of stressors these corals have experienced including bleaching events, hurricanes and disease outbreaks.”

Mote spokeswoman Allison Delashmit added, “This is a monumental milestone for Florida’s coral reef, coral reef restoration and conservation enthusiasts because it’s proof that resilient coral can be propagated and grown in a lab, replanted on a degraded reef, and reach sexual maturity within a few short years.”

The pregnancies demonstrate that Mote’s science-based coral restoration strategy, combining resilience testing and multiple growth/reproductive interventions, has been successful. The fact that they are spawning is the crowning achievement.

A restored mountainous star coral spawned in the August spawning event, the first time this has ever happened in Florida or the Caribbean. JOE BERG/Mote Marine Lab

A restored mountainous star coral spawned in the August spawning event, the first time this has ever happened in Florida or the Caribbean. JOE BERG/Mote Marine Lab

A restored mountainous star coral spawned in the August spawning event, the first time this has ever happened in Florida or the Caribbean. JOE BERG/Mote Marine Lab

In the wild, slow-growing massive species like the mountainous star coral, tend to grow less than 1 centimeter per year and can take decades to grow and develop from “baby” size to sexual maturity. Mote’s scientists have hijacked that process and sped it up using propagation and outplanting methodology called “microfragmentation-fusion” or “reskinning” that allows them to produce sexually mature mountainous star corals in as little as five years instead of decades.

“Not only can we increase live coral cover quickly with this method, but we can also reduce the time to sexual maturity,” Koch said.

The restored mountainous star coral is the first massive or mounding species in the world restored through fragmentation and cluster outplanting that has become gravid and actually spawned, Dealshmit said.

“Today, I have even more good news — we got them reproducing on FILM!” Delashmit said. “We were able to record these corals spawning in the wild, and it’s such a beautiful sight!”

The branching staghorn Koch observed is also the first Mote-planted coral of its species to reach sexual maturity and spawn. The colonies did so within two years of being restored to the reef, an observation that has been cited only once before.

Perhaps most encouraging is the fact that both colonies have proven to be resilient to global, regional and local stressors and still were able to produce gametes despite “incredibly hard conditions,” said Delashmit. The mountainous star corals endured a 2015 global bleaching event, a 2017 Category 4 hurricane (Irma), and a 2019 outbreak of stony coral tissue loss disease on that particular reef. The staghorn corals also survived Hurricane Irma.

“These findings provide hope for the recovery of Florida’s coral reef and for coral restoration science in general,” Koch said.