Billy Kearins isn’t new to serendipity. His workshop space-turned music venue-turned lifestyle brand Coast has been a product of hard work, and also, happenstance. The motto: “Coast. Live by it.” is something Kearins calls “purposely ambiguous.”

Kearins moved back to Key West from Copenhagen six years ago and was looking for a work space. Self-trained as a builder (of boats, boards and stages, among other things), upon return, he visited his old studio on Shrimp Road on Stock Island. “I figured I’d go back and see if my shop was available, where there was a group of studios,” Kearins said. “And literally that day I visited, they were knocking it down. A lot’s changed in five years.”

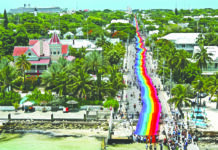

Instead, like any good islander, he went to have a bite and a beer. “I basically hopped into my buddy’s truck, and we were headed to Hogfish,” he said. They saw the lot on Front Street, and it had a “for rent” sign on it. “It was bigger than what I was looking for — it was just an empty gravel lot and the main building. But it seemed like it had a lot of potential.” Kearins (and company… a rotating cast of friends, craftsmen, and fellow artists) built it out, creating open-air studios, common space, and ultimately, a stage.

“During this time I developed the Coast brand,” he said, “But it wasn’t really a brand back then, it was a community of craftsmen by the sea.” Kearins describes those early years with some nostalgia, and it’s easy to look at the seaside gravel lot and imagine it animated with people creating things with their hands. He describes their Friday afternoon socials, cold beers, and the sounds of a local band (they offered up the lot as a free practice space). The work was a constant, too.

“During the first couple of years, there were a lot of building projects: local companies hired us to do artistic carpentry, anything from painting a mural to building a boat.” During that time, a Brooklyn artist named Duke Riley worked at Coast for a while, building bird coops and training homing pigeons. He ultimately trained them to fly from Havana, Cuba to Key West, “carrying illicit cigars and cameras to record the journey” (according to a New York Times story). Kearins describes it as a time of “renegade art.”

Art begat music. “There wasn’t this type of live music venue in Key West; there were bar gigs but not like ticketed shows.” Through parties and gatherings with local musicians, the idea of inviting bands to Coast began to bloom. Soon, Coast was hosting — and selling out — acts like Mason Jennings and G Love and the Special Sauce. “Everybody wondered how we did it,” Kearins laughed, “And it’s like, ‘You just have to ask.’”

This is the peak magic moment in the circuitous Coast story, if you could nail one down. “We were going on full cylinders, doing big projects, selling out shows, and the studio was full, and we were riding that wave for several years. … But I knew it wasn’t a sustainable model.”

He was right. The shows were paying for themselves but not making money, and Stock Island continued to be just a little too far to drive for Old Town Key Westers. The Key West Theater opened up, and began competing for big acts. That’s when Kearins felt it became “less interesting” — competition wasn’t what he was looking for, and he seemed happy that new venues were allowing for good music in Key West. Coast drifted out of the venue business with the same ease of drifting in.

“It wasn’t really a brand back then, it was a community of craftsmen by the sea.”

Then the story returns to where it started: Kearins was contemplating leaving the Stock Island lot, riding his bike down Whitehead Street, and he saw another “For Rent” sign. “I always liked Bahama Village, it was the first place I lived, and it’s the first place I had a workshop.” He called the number and within a week was in the new space, building it out, selling apparel off the front porch. “I took the leap,” he said, “and I figured, now it’s time. I could have waited, but that’s not really my style.”

They are now selling apparel and handmade skate and surfboards out of the Whitehead outpost. They are also hosting Yonder Mountain String Band at the San Carlos Institute on Sunday, Feb. 17. Coast continues to evolve: Kearins hints at a “strategic partnership” for new Keys-based ventures, and he took an East Coast road trip over the summer to scout new Coast locales. He’s not interested in exporting Key West, but rather finding each beach town’s own iteration of the concept. “I don’t like walking into a place in Brooklyn that looks like you’re in Key West.”

Kearins has his sights set on expansion and innovation, starting studios, work spaces, and retail spaces in “other funky end-of-the-road places.” He said, “I want to have a good solid presence down here, by which I mean still doing workshops, occasional concerts, and then a retail space, and we can use that to build other stores.” But expansion doesn’t mean popping up in every mall in America. “I don’t want it to be a false brand, where it’s a sticker or a label. And I always want to have an anchor in Key West. I picture Key West as the end of the road, and the only way you can leave here is by going up.”

Yonder Mountain String Band

A Coast Concert

San Carlos Institute

Sunday, Feb. 17 at 8 p.m.