The Beatles fought racism from a Key West motel. (You can read more about that at keysweekly.com.) You can also fight racism. While we celebrate Key West as “One Human Family,” we must not forget the island’s history of “un-human family” behavior, lest history repeats itself. Love Me Do is a weekly feature that invites readers to learn about the past and reflect on how their own actions and attitudes today might be viewed in the future.

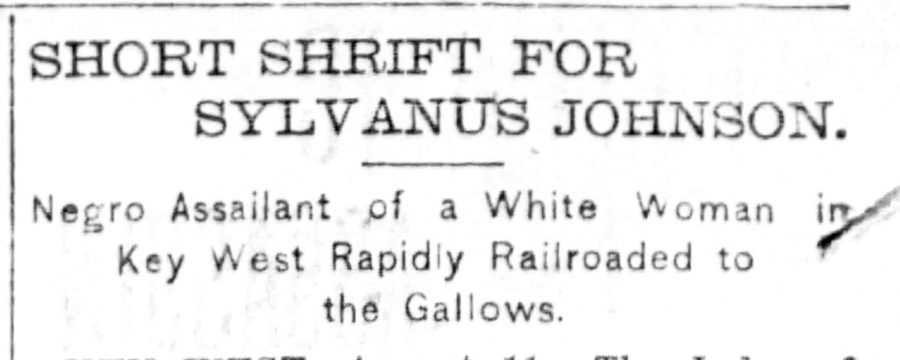

Racial tensions flared in Key West in 1897 when 19-year old Sylvanus Johnson, a black man, was accused of assaulting Margaret Atwell, a white woman, as she collected wild sapodilla by the salt ponds.

Citizens crowded the courtroom after Johnson’s arrest on June 24, 1897. The hearing was just underway when Col. C. B. Pendleton, a prominent white citizen and owner of a local newspaper, interrupted the proceedings by rising and asking, “Are there enough white men present to hang the negro?”

“Yes! Yes!” the group responded, and a white crowd moved in on the black prisoner. Sheriff Knight and his deputies drew their guns and held the crowd back while other deputies whisked Johnson to jail. Outside the courtroom, a black citizen called out to lynch Pendleton, and a group of black citizens rushed the white newsman as he drew his guns. Pendleton escaped in a carriage.

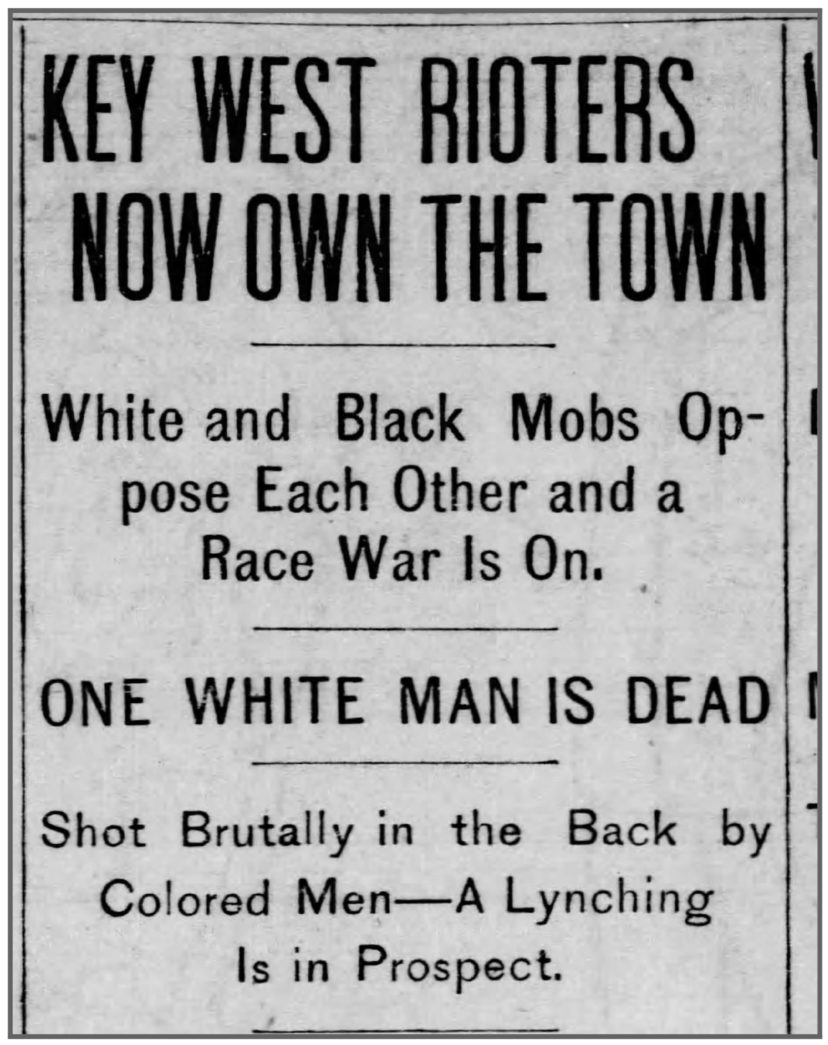

Word spread there would be a second attempt to lynch Johnson, and black men surrounded the jail to protect him, promising to shoot any white men that attempted to enter. William Gardner, a white man, was shot that night, and the Key West race riot was on.

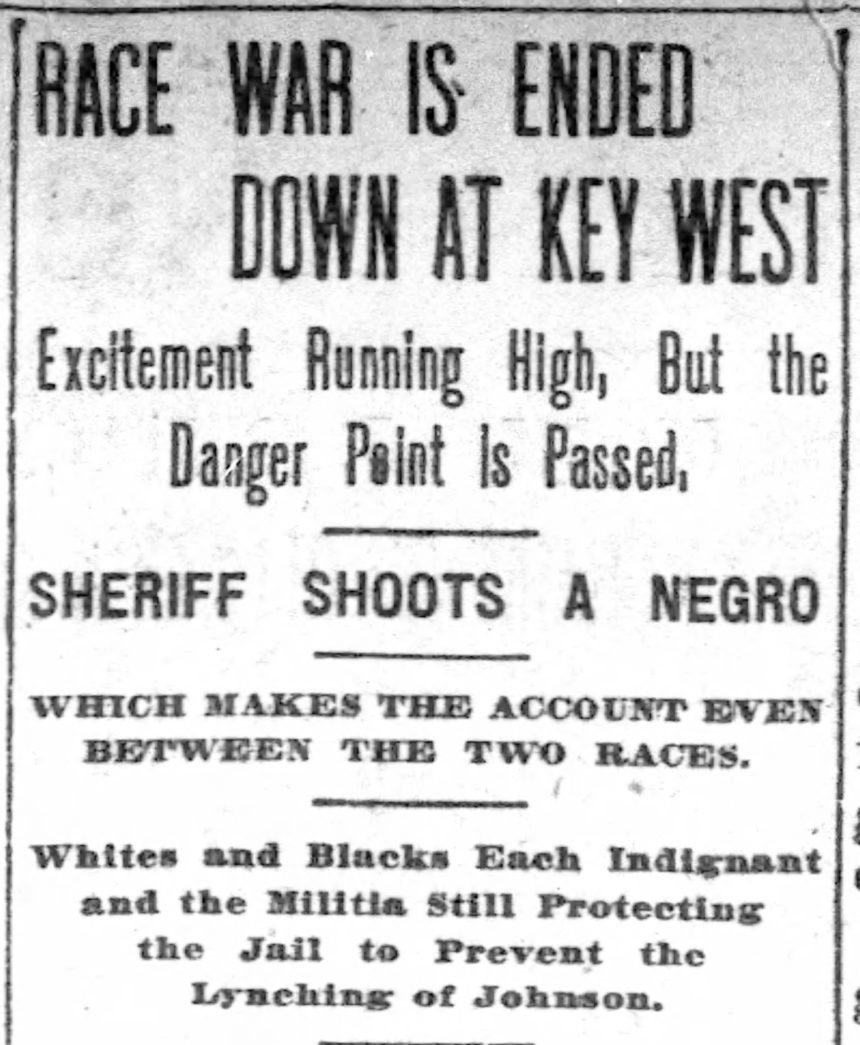

Sheriff Knight summoned a posse of 40 men, then wired the governor and asked him to order the local militia out. He also requested that the Secretary of War in Washington send in the national troops to protect lives and property.

Governor Bloxham telegraphed President McKinley, who called a meeting with his Secretary of War. Key West was on high alert for nearly 48 hours.

Still, The Buffalo Times reported, “There was no organized disturbance during the night, owing probably to the drastic measures taken by the Sheriff, who promptly shot down a negro in time to thoroughly awe the gang of colored men which seemed inclined to make trouble.” The headline declared, “Sheriff shoots a negro, which makes the account even between the two races.”

Newspapers across the nation blamed Sylvanus Johnson for the riots. Only The Sun, published in New York City, spoke out against Col. Pendleton.

“Several good citizens were killed or wounded as the result of Col. Pendleton’s officious and lawless act… He should have been the most zealous man in the island city to urge the maintenance of the law and respect for the Judge on the bench. Pendleton was allowed to go at large, with the resulting riot and murder. The troops were not asked to punish Pendleton and the white men…, but to… punish the black men who resented the conduct of Pendleton. Pendleton and the other white men who sided with him will never get into a court of justice, but the blacks who his indiscretion provoked will be apprehended and tried and punished.”

Indeed, several black men were arrested and convicted. After a short trial on Aug. 14, it took an all-white jury just 21 minutes to declare Sylvanus Johnson guilty. The judge ordered him hanged. Newspapers reported that upon hearing the verdict, “Johnson’s effrontery gave way, and he commenced to blubber and cringe, and in a half-crying tone said: ‘If God Almighty was a (black man) and had to be tried in Key West today he would be hung.’”

Perhaps Sheriff Knight saw the injustice. On Aug. 28, the sheriff took Johnson out of jail for a drive around the city.

The New York Times reports that the couple rode around to all the points of interest, and reaching Leon’s Saloon on Front Street, they “alighted and went in where they met a boon of companions. The Sheriff ordered drinks and cigars, and the strange spectacle was presented of a criminal under sentence engaged in the hilarity of the barroom with the highest peace officer of the county.”

Sheriff Knight took Johnson to his mother’s home next, where they socialized for an hour before returning Johnson to jail. The public was outraged and renewed their calls for the death of Johnson.

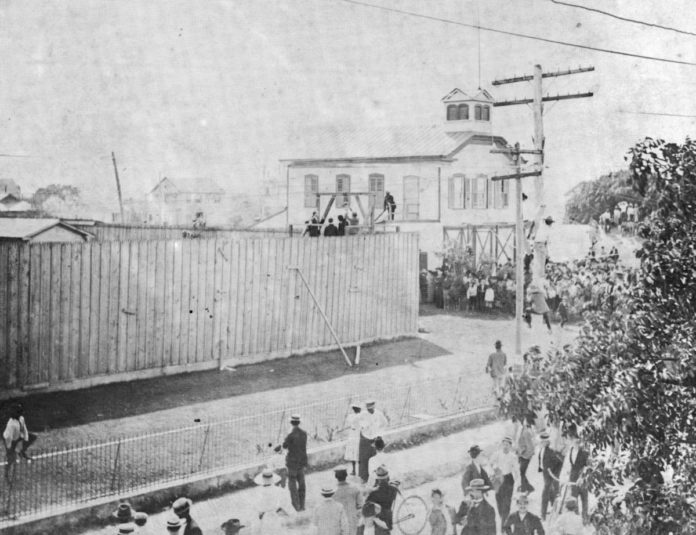

Execution orders were received, and deputies led Johnson to the gallows on Sept. 21, 1897.

As many as 5,000 people watched as he emerged from the jail singing, “Nearer, My God, to Thee.” Some reports say Johnson confessed, while others say he maintained his innocence and, in a short speech, blessed and forgave the officials, friends and enemies.

Sylvanus Johnson’s last words were, “Oh Father, I will be in thy kingdom soon. “

A black cap was adjusted over Johnson’s head, and at 11:32 a.m. Sheriff Knight sprang the trap door of the gallows. Johnson dropped 8 feet and 9 inches below the platform, but he didn’t die. The hangman bungled the noose, and the knot slipped from Johnson’s ear to his chin. He struggled violently for three minutes, then struggled again after 10 minutes had passed. At 20 minutes, Sylvanus Johnson was still alive. Sometime after 21 minutes, he died of strangulation.

Sylvanus Johnson suffered one minute on the hangman’s rope for every minute the Key West jury deliberated his fate. And though Sylvanus Johnson technically avoided the lynching called for by Col. Pendleton, make no mistake that his life still ended on a rope because of his skin color.