Editor’s note: This is the first installment in a four-part series.

If it hadn’t been for arsenic poisoning, Henry Perrine probably would have never ended up in the Florida Keys. Unfortunately, the poisoning happened.

He was born Henry Edward Perrine in one of New Jersey’s oldest towns, Cranbury, on April 5, 1797. The oldest of six children, Henry was an inquisitive child who liked to learn. Unexpectedly, his father died in 1813. Henry was 16. In order to help support his family, he dropped out of school, entered the workforce, and transitioned from student to teacher in a one-room schoolhouse. It was not what he wanted to do. Henry wanted to be a doctor. After two years of teaching, he quit and entered medical school.

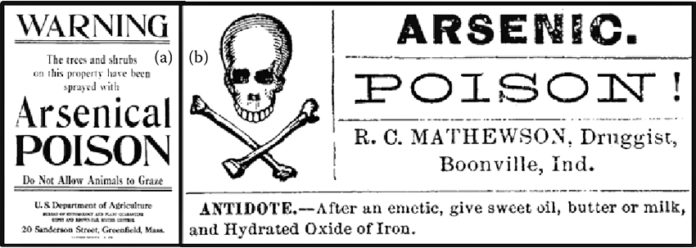

Dr. Henry Perrine graduated in 1820. He was 22. Not wanting to set up his practice in the relatively domesticated confines of an already established town, he ventured to Ripley, Illinois, in the Northwest Territories. To the people of Ripley, he would become known as their “li’l hard-working doctor.” He did more than tend to patients. The doctor also experimented with plants and herbs. One of those botanicals was Peruvian tree bark. He used the bark to make a tincture, and whenever he called on a sick patient, he would take a shot of the tincture to fortify his immune system. In addition to the tree bark, Perrine was experimenting with arsenic.

It was not long before the young doctor needed an assistant. In 1821, Perrine was called away on a medical emergency. As was customary, he went to his office, poured a shot of his tincture into a glass, and drank it before climbing on to his horse and riding away. Returning to the office, the assistant recognized the tragic mistake immediately. Perrine had taken his medicine from a glass used in an arsenic experiment. It had yet to be cleaned. The assistant saddled his horse and raced after the doctor.

Though Dr. Perrine was found in time, he never fully recovered. All was good as long as the weather was warm, but once the temperatures began to drop, his compromised system would begin to break down. It did not take long to realize he needed to move to a warmer climate. The first stop was Natchez, Mississippi, where he spent much of his time in the riverboat town setting the bones of those engaged in fisticuffs. While in Natchez, he contracted malaria, also known as yellow fever.

As he recovered from the illness, Perrine experimented with a new drug called quinine that was derived from the bark of the cinchona tree native to Central and South America. He took copious notes and, after recovering from the disease, submitted his work to the “Philadelphia Journal of Medical and Physical Sciences” in 1826. It became the most important paper on the use of quinine for 100 years.

Continuing to move south, Perrine went to Louisiana, but the winters were still too cold, and the doctor decided to go to his wife and growing family in New York. What was clear was that he needed to live somewhere warm that did not experience extreme seasonal temperature fluctuations. He needed to be in the tropics or, at the very least, the sub-tropics. At about the same time, the government announced it would seek applications to fill 100 consul positions representing the United States around the globe.

Based on climate, Dr. Henry Perrine applied to be the consul at Campeche on Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula. After waiting for a response for several months, Perrine was offered the job. His post would be stationed at Tabasco, Mexico, where his primary responsibility was documenting cargoes either being imported from or being exported to the United States. Perrine’s 10-year post at Tabasco began in 1827. Though Perrine and his family did not arrive at Indian Key until Christmas Day, 1838, his association with the Florida Keys began years earlier.

In part two, Doctor Perrine will connect with Charles Howe of Indian Key and Lighthouse Keeper John Dubose at Key Biscayne’s Cape Florida Lighthouse.