Editor’s note: This is the second installment in a four-part series.

Dr. Henry Perrine never fully recovered from the accidental arsenic poisoning. He felt fine during warmer months, but once the seasonal temperatures began to drop, his body would break down. Accepting the position of consul representing the United States on the tropical Yucatan Peninsula became a health-based decision. The 10-year assignment began in 1827.

The doctor’s primary responsibility at Tabasco, Mexico, was checking cargo being imported from, or exported to, the United States. His schedule offered ample time to explore the local villages, where he provided whatever medical assistance he could. He discovered that much of the medicine used was the product of local plants. Once the villagers understood the doctor’s interest in the local botanicals’ healing nature, and his willingness to help the villagers in need, they began to bring him samples. This root soothes stomach pains. This leaf is used for aches. This leaf is used for fever.

The villagers surprised him one day with a colorful parrot. The bird had been taught to say, “Dr. Perrine, Dr. Perrine!” Tickled by their gift, he sent the parrot home to his family in New York so they could hear his name echoing through their house in his absence, “Dr. Perrine, Dr. Perrine!” When the parrot arrived, the family wanted to give it an appropriately colorful red cage. The parrot, as the birds do, chewed and chewed on the cage’s lead-based painted bars. On the third day in its new home, the parrot fell to the cage’s floor and, as it convulsed, cried out, “Dr. Perrine, Dr. Perrine.”

Meanwhile, President John Quincy Adams sent a letter to each of the newly appointed consuls, requesting they document any plants that might prove beneficial to the United States. Perrine was the one in 100 who took the directive seriously. Not only did Perrine compile copious notes about the local flora, he noted seasonal weather patterns. He also shipped seeds and samples to horticulturally-minded friends in America, including the Florida Territory’s John Dubose and Charles Howe. Dubose, the lighthouse keeper at Key Biscayne’s Cape Florida Lighthouse, was sent more than 100 boxes of botanical samples.

In 1833, Perrine wrote, “We have testimony of the healthiness of Cape Florida in its most unequivocal form. The family of J. Dubose, consisting of eleven whites, and several negroes, has not had a case of sickness during the last seven years. The tenderest and most productive vegetables of the tropics are flourishing under his care. … The harbor at the cape … is easily accessible and a voyage to and from the northern states can be made easily. … Humanity requires that Key Biscayne should be made an available resort as soon as possible. … At Cape Florida, an association might be readily formed with a capital of a hundred thousand dollars which would furnish the buildings, gardens, and other conveniences requisite for the most squeamish visitor, and keep a packet running every month with passengers and effects from the north. The most luxurious accommodations could be profitably afforded at half the price paid in Havana.”

As he had to Dubose at Cape Florida, Perrine sent crates of botanical samples to Charles Howe at Indian Key. A hurricane in 1835 destroyed many of Perrine’s plants at Cape Florida. At Indian Key, the damage was estimated at $500 and included the destruction of citrus trees. The 1835 storm is particularly notable because it became the first hurricane recorded at Key West. Two additional events of note occurred in 1835. Halley’s Comet burned a fiery line across the Florida Keys’ skies, and hostile engagements sparked the second escalation of the Seminole War.

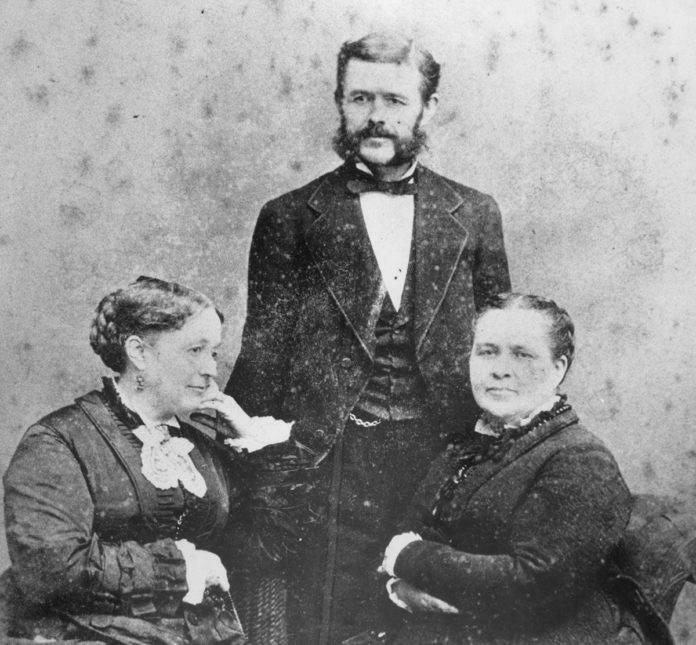

At the end of his 10-year post at Tabasco, Perrine returned to New York to be with his family. In December 1838, Perrine, his wife Ann, and their three children, Hester, Sarah, and Henry Jr., set sail for Indian Key. They arrived on Christmas Day. In a memoir written by Hester Perrine, she recorded her first impression of Indian Key: “I cannot forget our delight on first seeing this beautiful little island of only 12 acres. It was truly a ‘Gem of the Ocean.’ The trees were many of them covered with morning glories of all colors, while the waving palms, tamarinds, papaws, guavas, seaside grape trees and many others too numerous to mention made it seem to us like fairy land, coming as we did from the midst of snow and ice.”

Next week: Dr. Perrine settles into life at Indian Key, the Tropical Plant Company is formed, and Perrine provides commentary on the people of Key Vaca’s Conchtown and Key West.

Read part one: In search of warmer climate