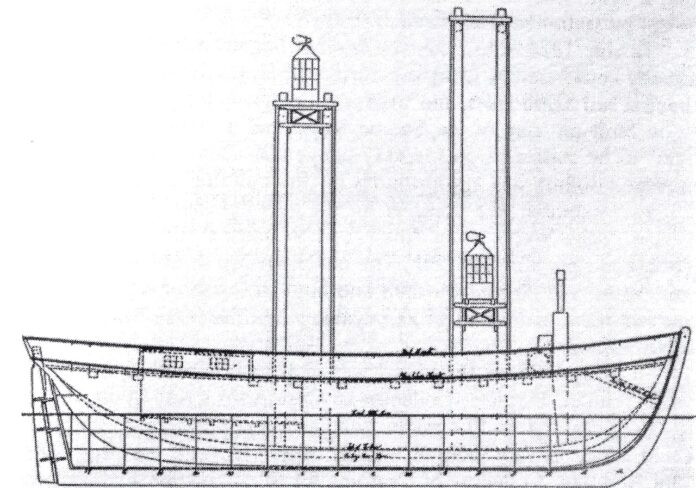

Before the skeletal, iron-pile lighthouses began to mark the Florida Reef, there were lightships. These were two-masted schooners equipped with lanterns and anchored out near the reef line to aid mariners in navigating hazardous waters.

Several lightships were employed off the coast of the Florida Keys, including those stationed at the Dry Tortugas, Sand Key and Key West. There were also two lightships anchored off of Key Largo at Carysfort Reef – though not simultaneously.

Carysfort Reef is several miles offshore of North Key Largo and quickly developed a reputation as a particularly treacherous tract of coral. The inherent danger it presented was one of the reasons it became one of the first reefs marked after the Florida Reef, the Keys, East Florida and West Florida became an official U.S. possession in 1821.

The lightship Caesar was the first two-masted schooner assigned to Carysfort Reef. The Caesar was built from the 1821 design by Henry Eckford after Congress approved $20,000 for its construction in 1824. By June 1825, the lightship had been completed, manned and was sailing for Key West, where its newly appointed captain, John Whalton, was waiting for it to arrive. The wait proved longer than expected.

The lightship sailed from New York on June 7. Two days later, it sailed into a gale and was wrecked on the Florida coast between Fort Lauderdale and Delray Beach. The captain and crew established a tent on the nearby beach where they were stranded for eight days before being rescued by Captain Churchill of the small schooner Good Intentions and delivered to Savannah, Georgia, on June 22.

Before they abandoned the ship and sailed away on the Good Intentions, the lightship’s captain left a note of “abandonment” on board the vessel and removed all of its sails. The message contained the time and date of their departure, because 12 hours after the ship was abandoned, it was salvaged by a wrecking crew from Cape Florida (Key Biscayne). The wreckers refloated the vessel and safely moored it in 24 feet of water after shifting the ballast around. The wrecker then set sail for Key West to acquire sails to refit the lightship.

When the Caesar arrived in Key West, repairs were made, a crew established and provisions loaded onto the ship. Ten months after the lightship wrecked along the Florida coast, Whalton sailed the Caesar up the Florida Keys and anchored inside of Key Largo’s Carysfort Reef at a convenient anchorage called Turtle Harbor, where the lanterns were first lit on April 15, 1826.

The future of the Caesar would not be smooth sailing or, in this case, smooth anchoring.

Ten months into their tenure at Turtle Harbor, one of Whalton’s crew decided he no longer wanted to be on the ship and staged a bit of a mutiny — or at least that is what contemporary newspaper accounts labeled his actions. When the crew member refused to follow his captain’s orders, Whalton placed him in irons. After the prisoner was secured, it was discovered that in addition to refusing to do as he was told, he was responsible for breaking the lightship’s alarm bell. The offender was placed aboard the Revenue cutter Marion, transported to Charleston and tried for his crimes.

Trouble on the lightship would not end with the arrest of the mutinous crew member during the Caesar’s relatively short career marking Carysfort Reef. A letter written by Whalton dated June 10, 1827, and delivered to W. Pinkney, the Collector of Customs at Key West, revealed a tragedy that took the lives of two of his crew.

Apparently, casks of fresh water were not regularly delivered to the lightship or, at the very least, not reliably delivered, and it was necessary for Whalton to send his crew off to fill their empty casks. The “Boat,” crewed by Hans Hansen and Thomas VanPelt, left the Caesar to fill five 60-gallon barrels and “Beakers” on June 5.

On June 10, the “Boat” was discovered “sunk with the sails set” by Captain Loft, who salvaged the vessel and returned it to Whalton. In a letter written to Pinkney, Whalton stated: “I hope the people are not lost. But I have but little hopes of them. Capt. Loft has been good enough to deliver me the boat & articles found. I hope you will satisfy him for the trouble as the Boat was lying on the bottom in two fathoms water. I am now bad off from the wants for Boat & water casks. You will excuse the short letter as the Capt. is in haste & I have one of my fingers cut so bad that I can’t write.”

The ship would not fare much better. In only a handful of years, the Caesar, too, would be lost. In 1829, Whalton ordered the anchors brought in, employed the schooner’s sails and set a course for Key West (and not for the first time). On May 26, 1829, the Caesar arrived in Key West for repairs. After a survey of the ship, the Collector of Customs, Pinkney, remarked that the Caesar’s timbers were “an entire mass of dry rot and fungus. I must say that there never was a grosser imposition practiced than by the contractor in this instance.”

A day or two later, the Caesar was condemned. It would not be the last lightship stationed at the dangerous Carysfort Reef. Next week, we will explore the story of Caesar’s replacement, the lightship Florida.