For the first time since the COVID-19 pandemic began, baby corals from the Florida Aquarium have made their way home to waters off the Middle Keys.

In a joint effort to promote reef restoration and combat a stony coral tissue loss disease outbreak that has ravaged Florida’s coral reef tract in recent years, the aquarium partnered with Layton’s Keys Marine Lab to reintroduce a total of 560 corals at a site near the Tennessee Reef Research Only Area off Long Key.

The small corals, all between 20 and 24 months old, were successfully spawned by the aquarium’s Center for Conservation in Apollo Beach, Florida. They are the offspring of parent colonies collected as part of the Florida Coral Rescue Project, an initiative designed to retrieve and preserve corals from the Lower Keys, Marquesas Keys and Dry Tortugas for gene banking and safekeeping before they could become infected by the deadly tissue loss disease.

“Coral spawning is actually a year-long process; they need to sense the change in water temperature with the season as well as the change in the length of day,” said Keri O’Neil, the aquarium’s manager and senior scientist of coral conservation. “So we actually have to provide them with all of those cues with aquarium technology. … Our tanks are programmed so our corals actually think that they’re in Key Largo, and they do tend to spawn right on cue for when they would in the wild.”

The hundreds of corals outplanted this week are split among four species: the boulder brain coral, the grooved brain coral, the symmetrical brain coral and the spiny flower coral. While the flower corals aren’t known as a major reef-building species, the aquarium was the first to successfully spawn and raise offspring of this particular species in a tank, correcting inaccurate assumptions about the species’ fertilization mechanisms in the process.

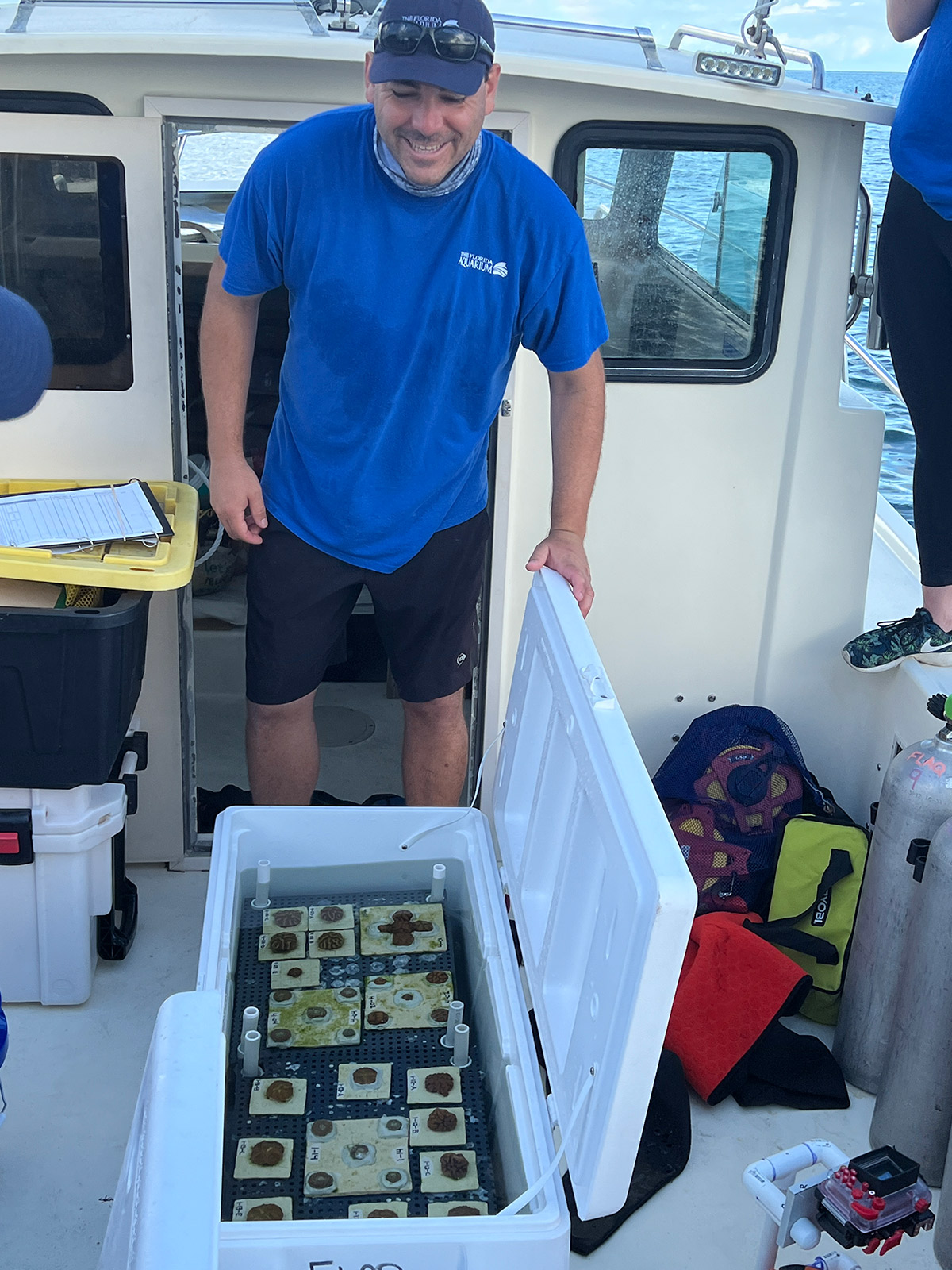

Just like any other animal released into the wild, the corals have already undergone a veterinary health inspection by staff veterinarian Dr. Lindsey Waxman. Now affixed to small ceramic tiles, divers used the week to attach the tiles to the ocean floor using a special cement mix. Once returned to the ocean, the corals will serve as a test for future outplanting events.

“We were able to raise these four species in pretty large numbers, and they’re disease susceptible,” said O’Neil. “We’re testing the waters to see if we can put susceptible species out into the Middle Keys and see how they do now that stony coral tissue loss disease is not at epidemic proportions anymore.”

On their way from Tampa to Keys waters, the corals were treated to a brief stay at the brand new seawater system constructed and funded by FWC at Keys Marine Lab to support coral restoration efforts throughout the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. This week was the first time the system was used for its intended purpose of aiding coral restoration.

“We fondly call it the halfway house for coral,” said Keys Marine Lab director Cindy Lewis. “We don’t do our own research, but we facilitate everyone else’s research. … (FWC) funded this facility, but they’ve also funded five years of operations, so it’s an amazing partnership between FWC and our home institution, the Florida Institute of Oceanography.”

In Lewis’ eyes, the first use of the system was a resounding success. Just ask the corals.

“These guys are so happy in this system, their polyps are out,” Lewis said, pointing to a tray in one of the holding tanks. “I’m seeing these guys look fuzzy, and that’s cool to see after everything they’ve been through driving here for seven hours.”

Brian Reckenbeil is a former FWC biologist who spent years living and diving in the Keys before becoming a coral restoration manager at the Florida Aquarium in late 2021. For him, the homecoming trip holds a special meaning.

“As a previous Marathon resident who has studied and seen the decimating impacts from stony coral tissue loss disease, it feels great to bring back hundreds of new genetically unique individual coral colonies to the local reefs,” he said.

All work was approved by the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary and was conducted under Permit FKNMS-2022-016.