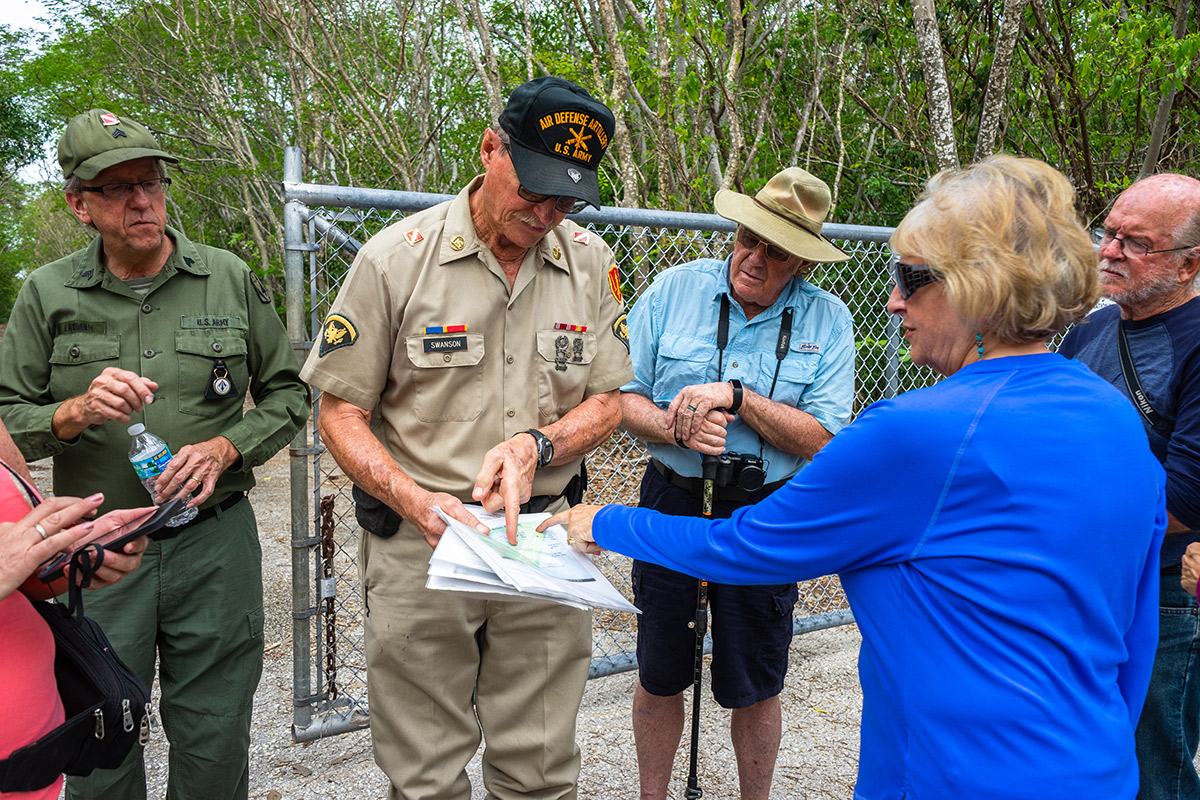

“Here’s your first security fence. There was a guard station over there,” says former Army Specialist Ted Swanson, pointing to what appears to be dense underbrush. “Beyond here, deadly force was authorized. It’s all overgrown, now.”

Swanson opens up the locked, chain-link fence and invites an eager group of civilians onto the old Nike Hercules missile base in Crocodile Lake Wildlife Refuge. “We’re walking back into history here,” smiles Jenny Ostrander as she enters and looks around. “I’m really excited about this! Getting to hear the history — it’s so cool. My dad was a SPC 5, so seeing the rank is just like, wow.”

Wearing his old Army uniform and holding an old map of the missile base, Swanson walks along the dirt road next to ex-Sergeant Robert Layman, also in uniform. The pair lead the group deeper into the wildlife refuge, stopping here and there to point out what used to stand where there are now bushes and trees.

“It gives me goose bumps,” said Layman about being back on his old base. “It’s like waking up from a dream. Forty years later, and I’m here. I’m seeing where I used to work — the buildings are still there, just dilapidated.”

The tour begins, and Swanson and Layman start with playful jabs at each other. “There were rail apes,” says Swanson, pointing to himself, “and scope dopes,” pointing to Layman. Swanson, a specialist 5th class in the U.S. Army, was an integrated fire control area radar maintenance chief. He was stationed at a sister missile base in the Everglades from 1966-68 to maintain all technical systems. Layman was a missile tracking radar operator from 1975-78 at this exact missile base. He’d track any launched missiles and guide them to their target. Swanson and Layman now conduct tours together through South Florida’s old Nike Hercules missile bases, telling the stories of their own lives, the role of these defensive military sites, and the history of international tension that brought them here.

The pair guides the group through the old battery, leading them into old missile launch control bunkers and onto the concrete slabs where barns used to house nuclear and conventional missiles during the Cuban Missile Crisis. “This is the missile assembly building, where missiles were put together and warheads assembled,” explains Swanson. “And this,” continues Layman, “is where we’d keep the active warheads.”

He points to a covered, cement cavern near a tree. “Looks like a critter must have gotten in there,” he jokes about the heavy lid, sitting ajar.

Four Nike Hercules missile bases, including this one within Crocodile Lake Wildlife Refuge, were constructed in South Florida in response to the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. The tension of the Cold War led the American government to believe that the U.S.S.R. was stockpiling missiles on Cuba to launch a nuclear attack on the U.S. The proximity of the island nation meant that Soviet missiles could target almost any American city. “The powers that be realized we had Nike Hercules missiles defending our northern border, but none here in the south,” says Swanson.

“So they got us in here to build these bases and become operational really quick.”

Layman adds, “The thinking was, if we ever got attacked by Cuba, one nuke would take out an entire squadron. We’d deal with the fallout later, but that’d be better than risking Miami or D.C.,” he continues.

“The time from launch to destroy was 90 seconds.” Swanson says. “These missiles are not like the movies, where the missile goes straight for the target. These were designed to go above a squadron, drop down in front to stop that plane, and take out the rest of the squadron with sonic and shrapnel. Highly effective.”

Both men describe the tense political atmosphere during the time they served.

“Cuba used to come two-three-four times a day, then skip a day, so we had missiles going up, coming down, up, down, constantly, because you just didn’t know,” says Swanson. He continues, “Castro, in one of his memoirs, talked about the U.S. like we were bigger than we were.” He laughs, “Which is good! Maybe he was intimidated by us.” He breaks it down further, “It’s easier to have a good defensive posture than to fight a war. That’s why we were here. We sent the message, ‘You really don’t wanna play with us,’ and maybe he heard it.”

Proudly, Swanson agrees. “By being so fierce, we never had to actually fire a missile from here. Good defensive posture saved us from nuclear war.” Layman chimes in, “If you’re 40 years or younger, you have no idea the work we did here, the pride we took in maintaining the peace. Sharing that history is my favorite part about these tours.”