Christina Romagosa is a research associate professor in the University of Florida’s Department of Wildlife Ecology and Conservation in Gainesville, Florida, but much of her work is in South Florida. Her research focuses on how ecosystems respond to invasive species, or non-native species that do harm to the ecosystem. Now, she’s focusing on invasive Burmese pythons in Everglades National Park — especially what’s inside them.

So what is it about pythons that got you hooked? I’m very interested in invasion ecology. I wanted to learn more about how this top predator, the python, can affect all the fauna [animals]. This one animal can affect the birds, can affect the mammals, and can have some effect on the reptiles. What happens when the Burmese python is present and how does that change the Everglades ecosystem?

Did you always know you were going to work in science? In college, I hadn’t come across any well-known biologists that came from my ethnic background and that made me feel a little alone. When I read Ariel Lugo’s interview (in my undergraduate biology textbook), I found it amazing that he was Puerto Rican and featured in the ecology section. I’m Cuban and I had never met anyone else with a Latinx background that had success in the field of ecology. It was very motivating.

And now you can be a role model for your students. I never think of myself as a role model, but it makes me so happy to have students pull me aside to say that my being here makes them feel like they can do this because we have the same ethnic background. I’m their Ariel Lugo!

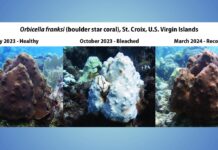

What motivated your studies on python diets? When we started this project, people had knowledge of the python diet. We knew that the majority of their diet was mammals. But we wanted to document and identify those animal groups that are most at risk of predation. Also, the insertion of a predator like a python into any ecosystem could cause changes in the food web called trophic cascades. We wanted to answer questions such as: How does an invasive species affect food webs in the greater Everglades? Does the python diet vary across space and time?

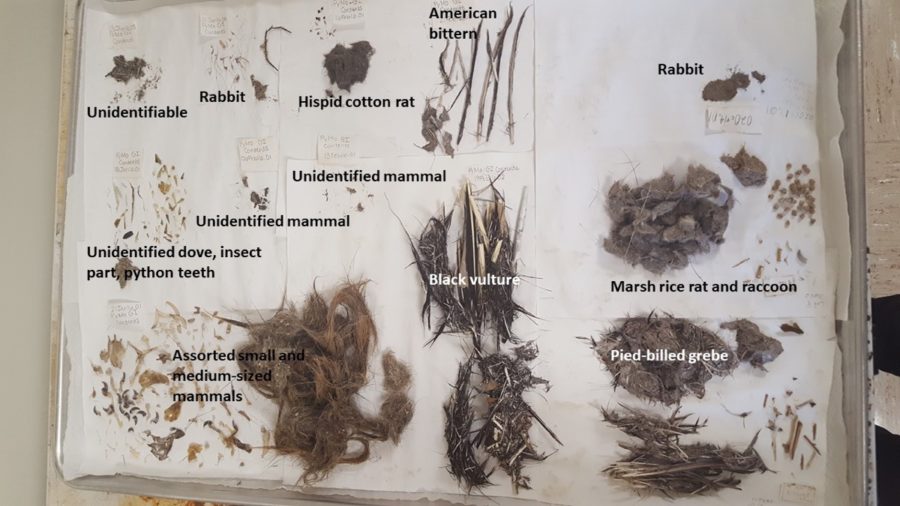

How did you get the pythons for your python diet project? I work with the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and the National Park Service, and as part of the collaboration, I receive pythons that are brought to the park after they are caught either on or near park lands. USGS and park scientists perform necropsies (an autopsy of an animal) and extract the gut contents. At our lab, we clean (a subset of) the contents so we can see the structures better and find out what those pythons ate. We find hair, teeth and feathers, and the animals are identified visually from those structures by looking through a microscope.

Identifying by eye seems difficult. You never use DNA? Project collaborators at USGS tried to extract DNA and it didn’t work. We don’t really know what’s going on, but if you are extracting diet contents from a python’s lower gut, the DNA extraction doesn’t work. We think that the python stomach must be really acidic and that completely degrades the DNA.

What have you found in the pythons’ guts? Pythons have a pretty broad diet, but within the lower part of Everglades National Park, such as in the Mahogany Hammock and Flamingo areas, pythons are primarily eating rodents like hispid cotton rats. Depending on where the pythons come from, we’ll find other mammals like opossums, wading birds, alligators and we’ve even gotten iguana.

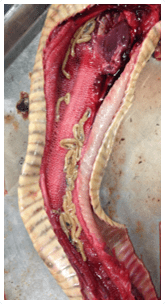

Tell me more about the crazy lung parasite in Pythons. Pythons here have this crazy lung parasite that’s native to Asia and they’ve brought it over to Florida.

It’s a pentastome species, Raillietiella orientalis, and is actually more closely related to crustaceans (like sea lice) than nematodes (worm-like parasites). Many snake species native to Florida are highly susceptible to infection from this parasite.

We found that R. orientalis infected 13 species of native snakes, and that the infection rate was actually higher in the native snakes compared to pythons. The native snakes were more likely to be infected by the parasite and contained more parasites per host, compared with pythons.

Do you know how native snakes are affected by these pentastomes? They (the native snakes) can have a lot of pentastomes in their lungs, and some have so many it can affect how they breathe. We found 77 pentastomes in one snake! More importantly, we are finding these pentastomes in native snakes where Burmese pythons are not found yet, so the native snakes could be giving them to each other.

-Antonia Florio, Everglades National Park